Over the last few years, Robert Runták's Collection has earned its rightful place in contemporary galleries in the Czech context. Regular borrowings and presentations of its acquisitions now place it among our most important contemporary private collections of European and Czech and Slovak art after 1990. Now rises an opportunity to present it in its historical breadth, which begins with Czech Art Nouveau and Post-Impressionism and gradually fills out at a remarkable pace, especially with regard to the art of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The aim of this exhibition is simple. To exhibit the best of the years 1900 to 1990, looking not primarily at this collection but rather through its prism at the history of Czech modern art in general. Perhaps in this way we will also catch a glimpse of something spiritual as well as of a social transformation of (not only) Czech society. Here are nine modern and postmodern signals. And they are "signals crossing like straws" (Ivan Blatný).

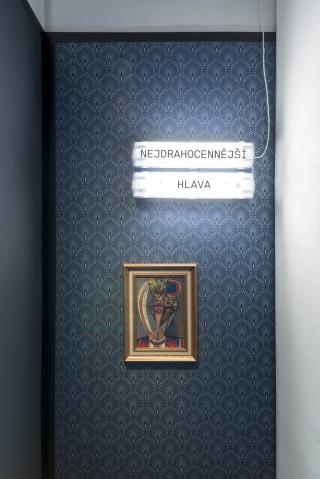

The Most Precious Head

"Illuminated with my eyes, / the most precious head," once wrote Paul Éluard, surrealist and Stalinist, widely read and admired among Czech readers. Ah, the wonderful 20th century! A century of heads, reason and unstoppable progress! And on top of that, the wonderful ideas of the 19th century: communism, rationalization of production, industrialization of life and death, scientific materialism, classless society, state nationalism, national hygiene, purification of races... Amazing heads = hundreds of millions of bodies in mounds of blood! "In my mind, in my head, this is where we all came from..." (Dynoro & Gino D'Agostino).

Sonata of Life

Czech art after 1900 naturally gravitated towards the "praise of earthliness" (S. K. Neumann). "You are in the garden at an inn outside of Prague / You are completely happy a rose is on the table" (Guillame Apollinaire). A celebration of life, of the pleasantness of home, but also pragmatism combined with the hedonism of everyday life and a resistance to big ideas - attributes of a small, emancipating European nation, which "undergoes history rather than creates it" (Petr Král). The Czechs simply and easily ruled what the Germans in Prague could only envy. That is, no longer "sentimental charm (...), but realistic life, the changeability in which divinity lies, that social, humane, world-friendly dimension towards life..." (Johannes Urzidil). Mariusz Szczygieł from Poland expressed it years later with a typical Czech irony: "earthly paradise on the surface" in the end always a little selfishly means: "make your own paradise."

The Century of Moloch in other words Existentialism

In the rear-view mirror of today, it seems utterly absurd and incomprehensible how 20th century humanity could have fallen for the lures of Communism, Nazism and Fascism in such large scale. How did it happen that millions succumbed to social engineering under the false flag of progress, nationhood and a happy tomorrow for future generations? Artists have depicted this dark, monstrous and bloody illusion, this insatiable colossus devouring everything around it, in their own way, but most often under the aegis of existentialism. It sounds rather proud: modern civilization, but as a deification of so-called progress and bright tomorrows, this "civilization" is in the end most similar to the cruel cult of the ancient god Moloch, who fed exclusively on human sacrifices. And his favorite meal was children.

Cubism or the problem of Surface, Shape, Time

The radical base of modernism is called the avant-garde. The first avant-garde revolution was carried out by the Spaniard Pablo Picasso and the Frenchman Georges Braque, who overcame the Renaissance perspective in an attempt to "solve the age-long problem of painting." Namely, how to represent the 3D reality of the world on a 2D canvas? And how else to get time into it all? Thus Cubism was born, which shook the history of art and gained special spurs in modern Czechia, "where all young painters are Cubists" (Apollinaire). To be a cubist was to keep past and present in an alchemical balance that celebrated the freedom of individual thought, feeling and imagination. The Czechs could not have chosen a wiser path into the 20th century." (Edward F. Fry).

The Glass House

The second avant-garde revolution was associated with the radical abandonment of the principle of imitation (in Greek mimésis), which was undertaken by the pioneers of abstract art at the same time as the Cubists: the Swede Hilma af Klint, the Dutchman Piet Mondrian, the Russian Vasily Kandinsky and the Czech František Kupka. Notwithstanding the fact that the roots of abstract art lie in the occultism, after World War II abstract became synonymous with art. Like cubism before the Second War. Everything came to the point where it seemed that future art, whether it was called Concretism or Abstract Expressionism, would be merely non-representational. The dream of André Breton, who wanted to live in a glass house, sleep on a glass bed and cover himself with a glass sheet, came true. Even the iconic starship Enterprise from Star Trek made it abroad with nothing but strict geometric constructivism.

Sexual Nocturne

The third revolution was launched by the Frenchman André Breton in the early 1920s, when he took the help of a psychiatrist from Vienna who, twenty years before the Surrealists, had already spoken of libido as a fundamental constructive but also destructive element of humanity. The Surrealists had not yet launched a general sexual revolution, but the dam of the instinctive imagination and the unconscious had been breached. The Surrealist "sexual nocturne" (Vítězslav Nezval) fascinated artists deep into the 1960s. And sexus became the most used strategy after 1945, next to the pure forms of the abstract cathedral. And, in fact, it has never stopped since. To this day, Marxism and psychoanalysis are still among the basic equipment of the leftist art historian(s).

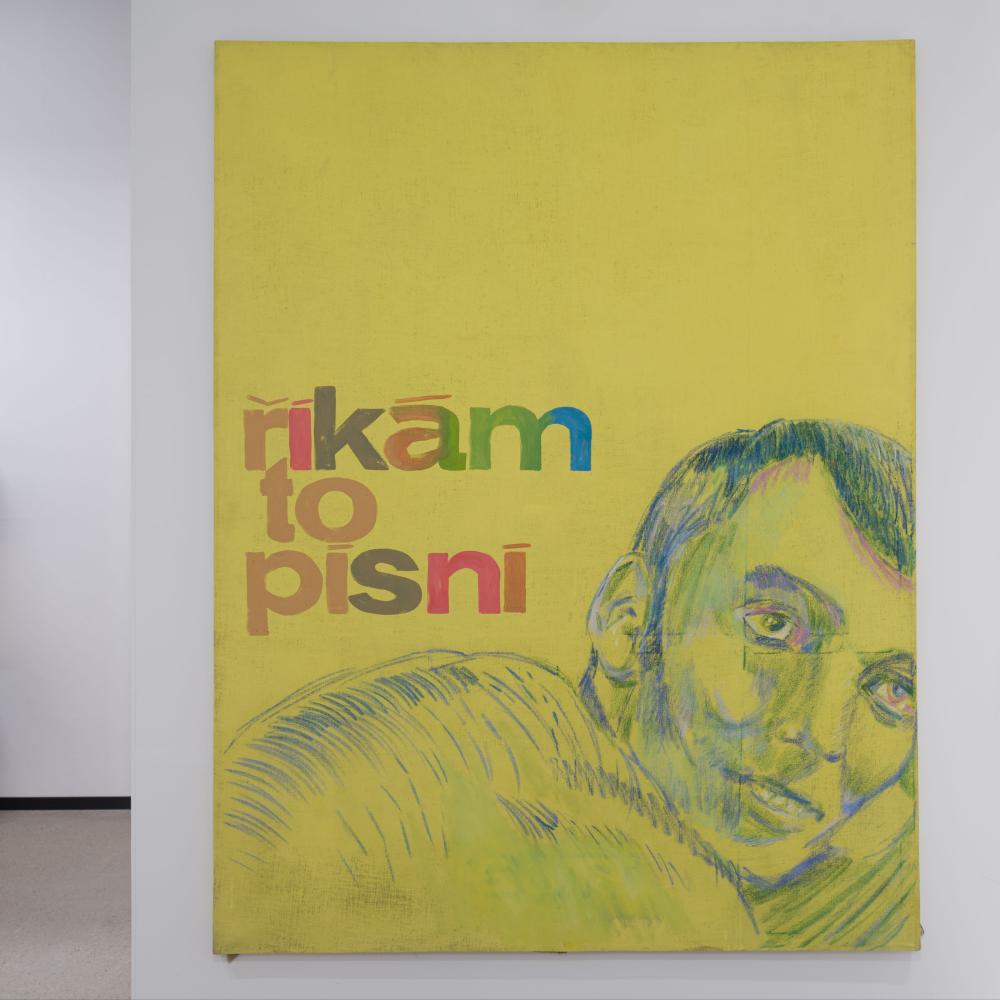

We are the Revolution

The delta of all 20th-century rebellions and experiments: the Golden Sixties. In its maelstroms, the final transfigurations of avant-gardes fulfilled their destiny, despite or precisely because they failed. Abstract art ended up in the toy-house of psychedelia and op-art, the sexual revolution was reincarnated in Marxist feminism, the Bauhaus ended up in Lettrism, the anti-art of Dada resulted in conceptualism. And yet one artist-prophet wanted to overcome the materialism and rationalism of the two hateful twins: capitalism and socialism, through artistic and pedagogical engagement (oh, how avant-garde!). With the actions of Joseph Beuys, the rawness of mythology entered art; the artist-shaman here wanted mainly to heal, the closed elitist modernism was to become "social sculpture" and open the way to the environmental expanded consciousness of the Third Way (the new occultism?).

Inhabitable bodies

In Czechoslovakia, as we know, all hope of the Sixties was run over by tanks driven by hard-faced Asians. Art and artists moved into "habitable bodies" (Petr Kabeš) of studios, yards and cottages. Another artist-prophet, Marcel Duchamp, expressed the exodus in 1970 without compromise: "The true artist of tomorrow will go underground." Yet what remained of the golden sixties, the "grainy torso of a giant body / scattered by time into time" (Petr Kabeš) could not be denied for long. Fortunately, the sausage socialism of Husak's timelessness created a grey zone where Artist did quite well, so much so that he discovered postmodernism, the remarkably viable corpse of modernism. And with this corpse came the Eliadean return of myth, ornament, joy, play, eroticism, beauty... "Anything goes", suddenly became true in late Biľak's Toughoslovakia.

Czech Heaven

"The land that has no heaven has lost everything, even itself...", sings Anna K. in an allusion to the radical de-religionization, atheization and vulgar materialization of Czech society in the second half of the 20th century. The accompanying phenomena of civilizational and ecological crisis. But there is still Art as "ontological praxis" (Jindřich Chalupecký); art that always offers new starting points; now without God, and even without a Man. In the end, all the rushing and dwelling on the little things on this Earth in Bedřich Dlouhy's painting installation Heaven is left only with a bunch of meaningless junk, supported by absurd columns of the past. After all, after every apocalypse the sun rises and clouds float out into the smurf-blue sky.

EXHIBITING ARTISTS

Karel Adamus, Eduard Antal, Daniel Balabán, Jiří Balcar, Juraj Bartusz, Mária Bartuszová, Štefan Belohradský, Vincenc Beneš, Vlastimil Beneš, Jiří Bielecki, Tomáš Císařovský, Josef Čapek, Karel Černý, Jarmila Čihánková, Jiří David, Hugo Demartini, Alén Diviš, Bedřich Dlouhý, Oscar Dominguez, František Drtikol, Emil Filla, Richard Fremund, Vladimír Havlík, Jiří Hilmar, Vlastislav Hofman, František Hudeček, Dalibor Chatrný, František Janoušek, Ludmila Jiřincová, Milan Knížák,Vladimír Kokolia, Jiří Kolář, Běla Kolářová, Stanislav Kolíbal, Vladimír Kopecký, Pravoslav Kotík, Jiří Kovanda, Radoslav Kratina, Jan Kratochvíl, Rudolf Kremlička, Jan Kubíček, Otakar Kubín, Jiří Kubový, Milan Kunc, František Kupka, Jaroslava Kurandová, Petr Kvíčala, František Kyncl, Josef Lada, Josef Liesler, Martin Mainer, Karel Malich, Pavel Maňka, Bohumír Matal, Vladislav Mirvald, Miloslav Moucha, František Muzika, Jiří Načeradský, Otakar Nejedlý, Rudolf Němec, Karel Nepraš, Petr Nikl, Libuše Niklová, Eduard Ovčáček, Marian Palla, Jaroslav Panuška, Antonín Procházka, Václav Radimský, Michael Rittstein, Jaroslav Róna, Tomáš Ruller, Zbyněk Sekal, Gino Severini, Zbyšek Sion, Vladimír Skrepl, Otakar Slavík, Jiří Sopko, Karel Souček, Jan Steklík, Antonín Střížek, Čestmír Suška, Adriena Šimotová, Václav Špála, Jindřich Štyrský, Václav Tikal, Karel Trinkewitz, Květa Válová, Aleš Veselý, Jan Wojnar, Ladislav Zívr, Jan Zrzavý

Curated by David Voda

Architecture by Mark Ther

Supporting programme:

24 8 / 18:00 Signal III: Guided tour

11 9 / 14:00 Signal III: Guided tour