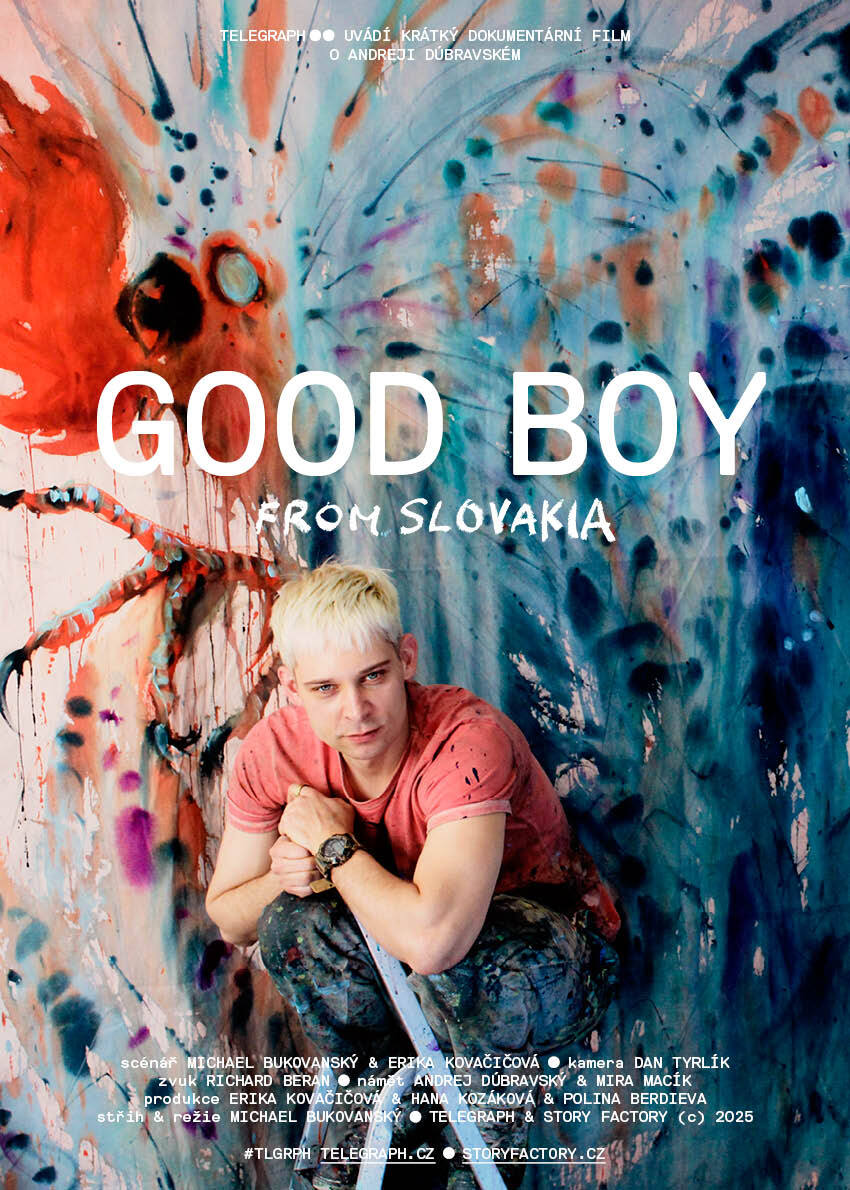

Michael Bukovansky returns with another short documentary, made in collaboration between the Telegraph and Story Factory, following last year's documentary debut Connection: Making the Indescribable. The new film, GOOD BOY from Slovakia, follows Slovak painter Andrej Dúbravský during the preparations for the Olomouc GOOD BOY exhibition, and reflects not only on the artist's work but also on current social events in Slovakia.

In 2022, you made the short thriller/comedy Parabens. How does working on documentaries, or specifically a film about Andrej Dúbravský, fit into the context of your work? Do you see any connection between these projects, or are they completely different approaches to filmmaking?

Making a documentary or a fictional film are quite different things for me. With Parabens, I thought up every detail and had full control over each of the individual components. I drew the storyboards, pre-selected the music, costumes and props and from the very beginning I had the overall rhythm of the narrative and the feelings I wanted to evoke in the audience at that moment in my mind. You can't prepare much for a documentary like that. One can only choose the situations one decides to capture, and then one can only wait to see what direction the conversation will take. In the case of GOOD BOY from Slovakia, we had the advantage that the whole situation around Andrej and the Minister of Culture Šimkovičová could be seen as an evolving story from the beginning. A story about a successful painter who represents Slovakia with his original work and who is condemned by the government officials in place because he paints something that reflects his sexuality, which they perceive as socially harmful. This conflict raises much broader questions about artistic freedom and human rights, and I am genuinely pleased that we can bring such serious and timely issues to light.

Last year, as a director, you released the film Connections: Embodying the Indescribable in collaboration with Story Factory. This year you made a film about Andrei Dúbravsky, who had an exhibition at the Telegraph Gallery in 2024 called GOOD BOY. How did you go from a spontaneous idea to make the first film to continuing to collaborate on the next exhibition?

It was the result of several factors. First of all, there was a demand from the Telegraph for another documentary following the warm reception of Connections: Making the Indescribable. This was sometime in the summer of 2024, when the GOOD BOY show was about halfway through. I suspect that it was then that the curators Mira Macík and Erika Kovačičová got talking to Andrej about making a short film about the previous exhibition, and Andrej wondered why we weren't making one about him too. Then just a word was given and a few weeks later we went with the cameraman Dan Tyrlík to Andrej's house in Slovakia.

The content of the new documentary is quite different from the film about The Connection. For example, was there a subject matter you were more familiar with and do you have a specific directorial method or approach to the documentary?

The film about the Connections exhibition features several artists who are united by their artistic method. It is composed of several statements by distinctive Czech painters and drawers, and it is in this diversity that I see its greatest contribution. With GOOD BOY from Slovakia everything was different from the beginning, because here the narrative focuses only on Andrej Dúbravský and the current political situation in Slovakia. Even before the Telegraph exhibition, Andrej was involved in a quite highly publicized dispute with the then newly appointed Minister of Culture Martina Šimkovičová. One of his paintings, which was part of an exhibition entitled Unbridled in the Slovak Radio building, allegedly offended her because it depicted two naked men kissing. It was then that I first sensed that we were facing an extraordinary story that would certainly be worth documenting, and when Andrej himself mentioned that he would not resist the political aspect of the film at all, the decision was made.

Minister Šimkovičová is generally quite an interesting phenomenon in today's Slovak political scene. People first knew her as a news presenter on TV Markiza, but then she moved to the internet television station Slovan, where news that could easily be described as disinformation is most often spread. The rejection of vaccines and the spread of Russian propaganda are just the tip of the iceberg of topics that Šimkovičová and her presenter colleague Petr Kotlár, who incidentally is now the government's commissioner to examine the process of governance and resource management during the Covid-19 pandemic, touch upon. The Slovak cultural scene has been literally shaking at its foundations under her government for the past few months, and the aforementioned disagreement with Andrej was just one of the first flags that foreshadowed the direction of her future decisions. As Andrej says in our documentary, "from the beginning it came to us as a joke too..."

You talk about how the cultural environment in Slovakia is shaken. In addition to changes in the leadership of institutions, there is also talk of censorship, homophobia, the art community is protesting...

As someone who is watching from the outside, how do you perceive this situation? Do you feel a deeper connection to it due to the proximity of Slovakia, or do you perceive it more from a distance?

I cannot say that I perceive the topic of free culture and the speeches of the highest state officials calling for control and censorship of art in Slovakia with a distance. The subject is quite personal for me also because my girlfriend is Slovak. I don't want to say that I can see into the workings of Slovak cultural institutions, but in my research, and especially in the necessary monitoring of the aforementioned disinformation channels such as TV Slovan or InfoVojna, it has become quite obvious to me that these media outlets work with strange interpretations of the facts, plant dubious narratives, or simply want to stir up resentment against anything labeled "progressive". The rhetoric of the presenters of these channels and their guests is based on the fact that they primarily want to divide society and make an enemy out of someone who does not actually have the slightest influence on the running of the state. It was all the more shocking for me to see how people from this disinformation scene began to divide ministries, offices and departments among themselves after Robert Fico's victory in the elections. The Slovak politicians featured in our film, such as Andrej Danko, Rudolf Huliak or Prime Minister Fico himself, are dragging so many cases behind them that didn't even fit into our film that it's really a wonder that these people are still sitting in their positions.

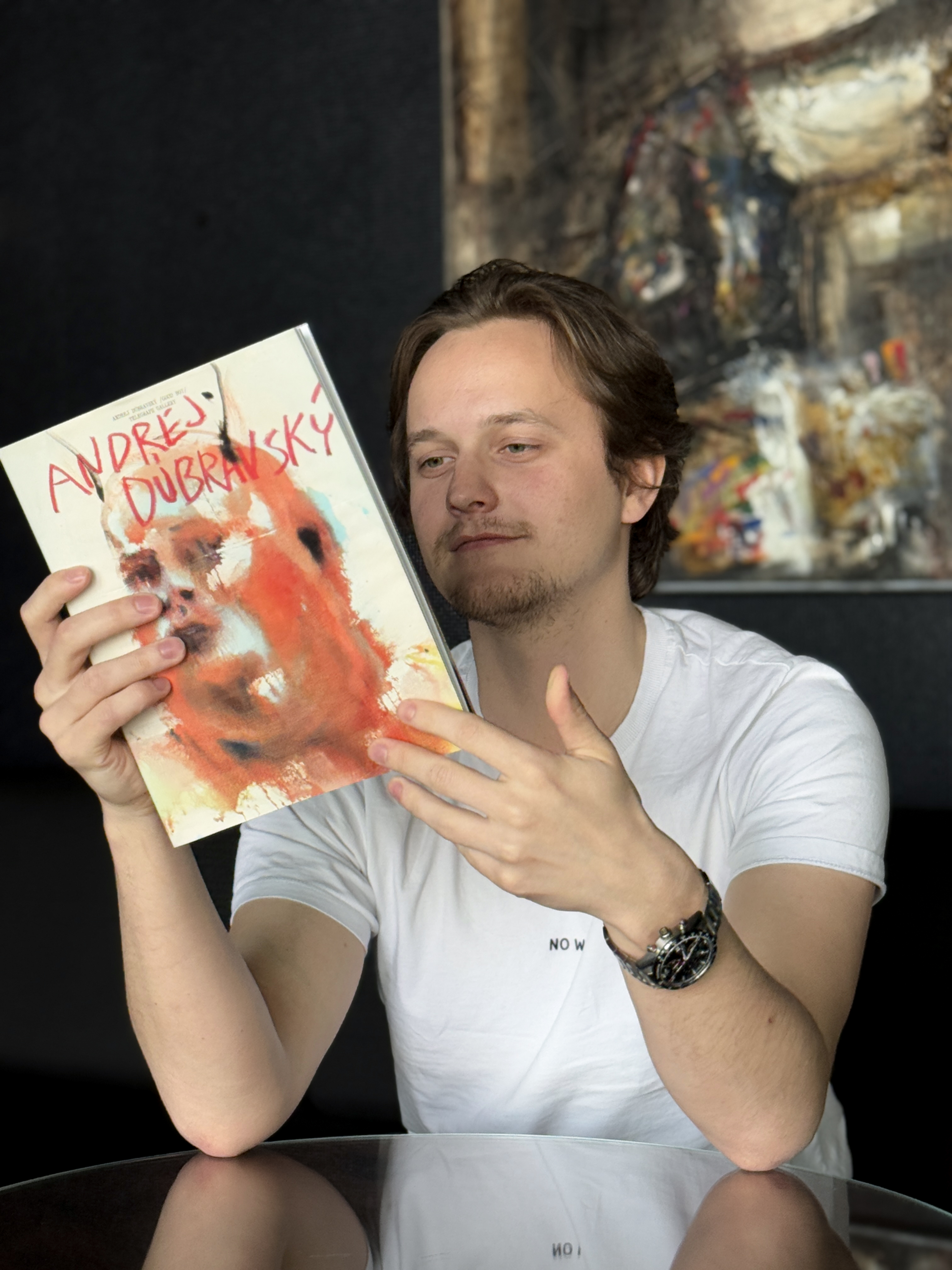

Andrej often interacts openly with his audience on Instagram and is somewhat used to the cameras. What was it like working with him from a director's perspective? Did his openness make the shoot easier?

I think what suited Andrei was that we developed a really comfortable atmosphere where it was just me, him and the cameraman. During the day, we would sit on his terrace, chatting, looking under his hands as he painted in his studio, or as he made us breakfast from the eggs his chickens laid. I remember him telling us point blank that some TV crews always wanted to come to his house to catch him at work and interview him, but he always refused all of them in front of us.

But at the same time, Andrej didn't know me before and must have been a little nervous about what the outcome of such an ambitious and politically-minded film would be. It was also clear that he didn't want to appear boring, so he joked a lot during our conversations, but was always very matter-of-fact and natural when it came to serious topics. His speech, along with the comments of curator Erika Kovacic, became the glue that held the film together.

Capturing current political and social issues in a documentary can be tricky. When balancing Andrej Dúbravsky's personal story with the broader context, what was the most challenging for you?

We wrote the script for the film together with Erika Kovačičová, the exhibition curator and Telegraph Gallery producer. I traditionally took on the role of director and editor. Due to the difficulty of the topic, it was clear to me that I could not underestimate the preparation before filming, however, I have been interested in political events in Slovakia and the disinformation scene in general for a long time, so this topic was not completely unexplored for me. Another advantage was that the protagonist of the film is Andrej, who has an extraordinary charm and during the interviews there were often funny lines. He could have pulled off a feature film. The whole atmosphere during the filming was very relaxed and even though we talked about serious things, we had a lot of laughs together. The fact that we didn't have a big crew and there was nothing to tie us down production-wise definitely contributed to that. At the same time, it was obvious that Andrej cared about making the documentary a success, so he let himself be guided at the appropriate moments and had no shame in sharing anything with us. So in terms of script and editing, the most challenging parts for me were the parts dedicated to the political situation. The difficulty stemmed from the fact that the ills of the Slovak political scene can be seen from several perspectives. In the end, we decided to focus on issues of freedom in artistic expression and human rights, with an emphasis on the position of the Slovak LGBT community, of which Andrej is a part.

The situation in Slovak politics often changes from day to day. Did the concept of the film change during the filming process compared to the original idea?

Did the constantly evolving political context in Slovakia influence its shape?

The situation did evolve during the six months that our documentary was being made, but people did not change their positions, despite loud protests and new cases that kept popping up. Rather, during the production and post-production process, we were always looking for new ways to add more to the film and what else we should highlight. Week after week, something new, more or less bizarre was happening, and still is happening, around the minister and her colleagues from the Fico coalition, which at least makes one raise an eyebrow. However, it was a pleasant revelation for me when I read my own text from the beginning of the summer of 2024, where I presented the general idea and theme of the then just-intended film GOOD BOY from Slovakia, when my crew and I had not even one day of shooting behind us. I went back to that text after I finished editing the film and I found that we had fulfilled exactly what we had promised and what we had wanted from the film in the first place.

What role do you think documentary film plays in a time when freedoms are being curtailed? Do you think films like this can make a real impact on public opinion? Do you think that the Slovak Minister of Culture would even see the film, and what kind of reaction would you expect from her?

If the Minister ever sees our film, or learns about it, I think from the kind of rhetoric I've observed from her that she would simply accuse us of political activism, which is something she thinks doesn't belong in art, and therefore doesn't belong in film. In her position, that kind of thinking alone is reprehensible. When editing the film, I also worked with footage from the National Council of the Slovak Republic, for example, or its official press releases. I could hardly be accused of distorting her speeches, or perhaps taking some sentences out of context; in short, sometimes truly disturbing statements come out of her mouth. I wanted them to be heard in our film. The viewers of TV Slovan live in a bubble and those who don't watch TV Slovan often have no idea what statements the performers make. Our film depicts Andrej Dúbravsky in a very strange time when Slovak society is divided, but it shows above all that one side of the political spectrum simply benefits from stirring up hatred and artificially creating problems, and thus wins the votes of the electorate, which is all the sadder.

The role of documentary film in such a politically strange time is best summed up by a quote from one of my favourite films by Romanian director Radu Jude: "When Athena exhorted Perseus to kill the monster, she warned him never to look at its face, but only at the mirror reflection in the polished shield Athena had given him. Perseus then, following her advice, cut off Medusa's head. The moral of the myth is that we do not and cannot see the real horrors because they paralyze us with blinding fear. The film is Athena's polished shield."

The film relates more naturally to the visual arts, but the crisis applies to a wide range of art. Slovakia has also addressed the crackdown on film funding when it comes to promoting LGBT+ issues. How do you perceive the situation in the cultural world in Slovakia from a filmmaker's perspective?

In our film, we directly point out that some members of the government coalition are trying to push for the suppression of sexual minority representation in films and in the arts in general. My basic position coincides with Andrei's view of the situation - art should be completely free and politicians should not have the slightest influence on it. At the same time, I fundamentally disagree with Minister Šimkovič's view that politics does not belong in art. I am absolutely astonished by such a view of the situation, because politics in a democracy is fortunately part of our lives and I consider it a natural right to express my opinion on it. When it comes to an artist, whether it's a painter, filmmaker, playwright or actor, they all have the right to express themselves through the medium they choose.

Where would you like a film to have the most impact? Is it aimed more at a festival audience, the wider Slovak society, or perhaps the international scene?

We are aiming directly at a specific audience, but the connection between visual art and the political aspect will certainly not be a topic for everyone. However, Andrej Dúbravský is undoubtedly an outstanding painter of world-class stature and the themes he addresses in his work are not something that should have any negative impact on the rest of society, quite the contrary. In contrast, the high-ranking politicians who would prefer to control his work, or ideally ban it from being exhibited outright, are perpetrating a division of society. I would be happy to see the film reach as wide an audience as possible, and a tour of festivals will certainly be part of that. I'm most looking forward to the upcoming screenings in Slovakia, where I suspect the post-screening discussions will be the most passionate.

Films you've directed are gaining a firm foothold at the Telegraph, is there another one in the pipeline?

We already started work on another short documentary in March, this time focusing on the now-concluded exhibition Signal IV: The Eighties. We want to look into the Czechoslovak art scene of the 1980s and we have already promised the participation of some very big names in the Czech art scene. However, the production of this film is only at the beginning, so I won't reveal anything else for now.